LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT: Amanda Green Looks Back at Writing ‘Swing’ (Part 2)

October 13, 2023 by Marisa Roffman

Credit: NBC

[In honor of the 15th anniversary of the LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT episode, “Swing,” Give Me My Remote is looking back at the hour with writer Amanda Green. Click here to read part 1 of the interview.]

With Elliot (Christopher Meloni) desperately trying to balance his home and work life in “Swing,” his attempts to save his daughter, Kathleen (Allison Siko), from herself as she was battling a newly diagnosed mental illness had unexpected consequences—he wound up alienating his wife, Kathy (Isabel Gillies), and his partner, Olivia (Mariska Hargitay). After he went rogue and turned in evidence that would guarantee Kathleen would be charged—and medicated—Olivia set about trying to help in her own way.

Here, Green talks about Elliot’s spiral, the mystery of the final “Swing” scene, Bernie’s legacy in the L&O world, and more…

Green’s chair on location. (Photo courtesy of Green.)

Elliot is on an island for much of this episode—estranged from both Kathy and Olivia, self-destructing, at times, as he tries to help Kathleen by whatever means necessary. Why was that the version of the character you wanted to explore here?

My family is not without its share of addiction and mental illness, as so many of us writers come from places of conflict. But for me, as a clinician, I always saw the behavior of Elliot Stabler, the rage, the explosivity, the drive, all the things that were presented—and this is a different conversation about copaganda—as good things…I always really approached that as a symptom, not as the character. Where is this coming from?

I started to creatively unpack where his rage might come from, as more than just as a cop, but also as a human. You start looking into the relationships and how they’re important to him. To me, it was, “Here’s a woman [in Bernie] who explains a lot about who he is now, being reflected through the two most important women in his life today.”

There was sort of this sort of triangle of women in his life. There was always Olivia and Kathy, and how was he juggling between these two women? And [now] here’s the third point of that tripod to explain why. To me, I understand why he’s married to Kathy Stabler [at that time] and cannot leave.

I wrote a [season 9] episode [“Paternity”] where Kathy has given birth, with Olivia [by her side], in a car. Here are these two women who are both in love with the same man for very different reasons—and experienced very different versions of him. And what’s that about? When I read back over the script, I remembered this moment where Benson basically called out Stabler on his explosivity, [implying to him] you need a shrink. I don’t think we ever got to say that [before]…when John Greene wrote the Mary Stuart Masterson [sequence in season 7’s “Ripped”], it was still very brief. This is a man that needs therapy and the culture of the LAW & ORDER universe [at the time] wasn’t one where the cops go to therapy.

The tremendous wounds we got to write about in “Swing”—when I re-read it, I was like, Jesus, I really laid on all this stuff: Your mother broke your arm. Your mother threatened to kill you. Your mother smashed your sandcastles, even now as a grown-up. Here’s the chaos of living with a mentally ill parent, which I did…I do know from personal experience how that unmoors you. And it’s probably why my first career was as a therapist.

I do think taking Stabler to low points was something I rather enjoyed doing, because I think when his character got to that place of vulnerability, and stripped down past the performative machismo and aggression, Chris was at his most brilliant.

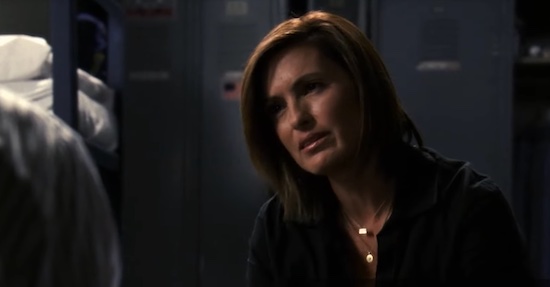

(Photo credit: Screengrab.)

Speaking to his vulnerabilities, the one real moment we see Elliot break is in the conversation with Olivia in the cribs: She’s mad and hurt he didn’t tell her about Bernie, he’s defensive until he finally gets vulnerable and acknowledges he’s in over his head—but she’s still mad, so he snaps back into a defensive space. What were the challenges in balancing the rhythm of that quasi-fight?

Writing those types of scenes, where Benson and Stabler dealt with big emotions—whether they were fighting or whether they were dealing with their feelings for one another—when they are in those big moments, I think for me what always was my guiding principle is that these are two people who want to hold each other…and can’t.

In this case, I think if there was a subtext to the scene for me, it would be Stabler needing to be held because he’s falling apart and Benson being so hurt, so betrayed, by this huge gap in intimacy: “You never told me this.” This is infidelity on the same level that sexual infidelity would be in a traditional couple, right? All these two people have is their emotional intimacy. To me, I remember feeling that way all the time—you have to understand that when this is all they have, how much those wounds cost. You’re writing a couple in every other way but the sex and physicality.

And this is a huge wound. All of Elliot Stabler’s life is defending against the chaos of his childhood. This is what happens when your mother can’t be a good enough mother, to steal the therapeutic phrase from DW Winnicott—that’s all we have to do as parents: be the good enough mother. Not fail. But most of the time [it’s simply] be good enough. And [Bernie] wasn’t. She couldn’t be.

What does that do to the grown man who then only has, as their parent they identify with, the controlling, domineering parent? That’s who you actually model on. If your mom isn’t there, especially in my generation—which is very much the character’s generation—what do you get? You get this.

That is what it is like to live with or love someone with a mental illness. It is to retreat into safety. Even when safety is calcified goals like [Elliot’s father preaching], “What it is to be a good man and a good cop, Elliot Stabler.” Sometimes, [you end up] being more like dad when the alternative is “I’m going to shatter your arm into pieces.”

Which is also not how it works. The character, at least at that point, was still trapped in this frame of reference of, “Either I’m crazy like my mom or I’m like my dad.” And that’s the way a little kid sees it. And there’s some of these things I don’t know how you bounce back from. There are things in this script where I was like, “Oh, wow, I was working out my own issues.” It’s interesting to go back there and look at this stuff, now, from a different point in my life, and go, “Oh, that was me processing my own trauma.”

I think at the time I was writing [“Swing”], I was a little further down the path than Elliot Stabler was in processing what that meant. But looking back now from way on the other side of that journey, 15 years later, I think if you don’t treat the wound, it festers.

[What helped with leaving my job] working with largely women and children who were the victims of sexual assault, domestic violence, and child sexual abuse—and knowing that I was making lives [there] not perfect-better, but somewhat better—was the fact that I could write about trauma and abuse through SVU. It was not directly impacting people, but indirectly, passively, letting people see that even with their experiences—whether it was with sexual assault, with mental health, or with childhood issues—they were not alone.

I talk a lot about the power of storytelling to affect social change. To me, the unsung story of SVU is not in how many hundreds of episodes that show has been on the air, or the careers it launched, both in front of and behind the cameras. It’s in all the conversations that I have had with people who have told me that the show reached them at a time in their life when they thought they were dealing with something alone, whether it was an experience of a sexual assault, or where they were dealing with their pieces of their own identity, maybe their sexual identity, maybe their gender identity. Maybe their role in their family. And the show said to them, “I’m not crazy.” The show says to them, “No. Lots of us. Come on in, the water’s warm.” That passive creation of a therapeutic space for people wrestling with big s— in their lives—that’s why the show is still on the air.

And when you were watching it in the early 2000s, where [else] were we talking about queer lives? We weren’t. Even imperfectly. Oh my God, we made lots of mistakes, where we were not yet evolved in our thinking. But we were showing people that if they were the outlier in their community, maybe they were in the wrong community, but there was a place for them.

When Bernie and Kathleen are speaking, Bernie says if Elliot hated his daughter he would walk out of her life. (Like Bernie feels Elliot did to her.) In the aftermath of Meloni’s exit from SVU, some have recontextualized that line—what do you recall about your intent with that scene when you actually wrote it?

I don’t remember the writing of that line, but looking at it [in the script now], I go, “Oh, I totally know what I was trying to do there”—which was reflect Bernie’s pain at him walking out of her life, without centering herself.

She has to, for herself, wryly say, “Oh, if he hated you, he’d cut you out of his life.” Because that’s what he did to her. That is how she experienced it. She feels like he hates me, he has walked out of my life. And to me, that’s her trying not to make the moment about herself, but still acknowledge the pain she’s in. That is her reality.

That is one hundred percent, in my creation of the story, that delicate balance we do when a wound hurts so bad we have to say, “Look, I’m bleeding, but also realize it’s not my moment.” I think that’s what parenthood is. And if anything, that moment to me is about trying to show that she actually is a good parent, in how she’s interacting with Kathleen.

She’s not doing the narcissistic thing, which is basically what Elliot accused her of, where [he implied] it’s always about you and what you want. What she could say in that moment, if she was narcissistic, was, “Oh no, honey, He doesn’t hate you. Let’s talk about me. I mean, he hates me. He kept me out of his life. He pretends I’m dead. He doesn’t even tell his partner I exist.” That’s stealing her light. But no, she’s perfectly present for Kathleen.

This is the glory of getting the second bite [at parenting] as a grandparent, I hope, that she can be there for Kathleen in this moment in a way that she couldn’t maybe be there for her own kid. But she’s not pulling focus. She’s letting the moment sit in Kathleen’s needs and Kathleen’s fears. And yet can’t help but let out [a bit of her pain].

And, by the way, Kathleen doesn’t react to it. Kathleen doesn’t say, “Wait, is this about you?” The scene just plays on. Kathleen can’t see Bernadette’s pain because she’s howling too much [with her own pain].

Elliot as a carrot. (Photo credit: Screengrab.)

The episode ends with Kathleen choosing to get help after her talk with Bernie—though Elliot is unaware of why she changed her mind. When Elliot questions Olivia, she simply says, “Maybe God remembered how cute you were as a carrot,” alluding to a photo Bernie showed her. In your mind, did Elliot figure out what happened? And how did that carrot photo come to be?

Back in the days of low-tech—which this was—whenever we had to create a photo that didn’t exist, it was always a big deal. We didn’t have AI de-aging software or anything; it was literally someone in the art department with an X-acto knife. And I remember asking Chris for kiddie pictures of himself, and he put us in touch with his mom. His mother—again, 15 years ago; she didn’t have digital photos—basically photographed pages from the family album.

We were very limited in what we had. We had to basically find a stock image of a kid in a stupid costume that we could then buy the rights to and then do some sort of editing so it looked right. We were looking through all the available shots and thinking okay, we have to literally float his head into something, what can it be? And the art department showed me choices and I fell in love with the carrot because it’s absurd.

Now, of course, these days you can freeze frame and blow that up and really look at it. Back then, it was going to be on screen for a blip. But there was something about that God-awful homemade carrot costume that really spoke to me. You know the old phrase “a face only a mother could love”? That’s a costume only a mother could love. From any aesthetic standpoint, that is just terrible. But the homemadeness of that moment and creating this picture [worked].

In the writing of that line, I really wanted Chris to be lost in the mystery of it. And maybe the character remembers that he played a carrot in that Thanksgiving pageant, or maybe he doesn’t, or maybe it strikes something deep down. I just wanted a moment where he didn’t know she did it or didn’t do it. But it hints at the potential for putting it together.

[Elliot] is a cop, he solves mysteries. And the mystery of “God remembered how cute you are as a carrot” is very much the way I talk. But it was a mystery that he could solve. And I remember fighting for that line. Not with [then-showrunner] Neal [Baer]—we never had to fight with Neal about the creatives—but there was always someone, whether it was a director or a producer.

But I wanted there to be the possibility that he could [figure] out what happened, but that she would not tell him. A version [of the episode] where she says, “I met your mom, she’s pretty cool”—no! She was deflecting credit from the moment, but also doing it in a way where if you’re really smart, you’ll put it together.

It’s the equivalent of an Easter egg for the character: here’s the answer, if you want to know. The only way Olivia Benson knows that he was a carrot in the Thanksgiving pageant is if she talked to his mother. And she’s not telling him that, [but] she’s not lying. Because also, again, it’s about their relationship. She’s not going to lie to him, but she’s not going to tell him the truth, either.

And Olivia gave her word to Bernie that she wouldn’t tell Elliot his mother helped.

She gave her word to Bernie. She’s not going to tell a lie, because they have a relationship, she and Elliot.

[“Maybe God remembered how cute you were as a carrot” is] one of my favorite lines I’ve ever written, so I actually have it in a frame in my office—I haven’t had it up in a while, but I haven’t let it go, either….it was on my wall at SVU for years and at other offices [after].

Burstyn in “Swing.” (Photo credit: Screengrab.)

Was there anything else memorable about filming this episode?

We shot in Rockaway Beach. We shot all the scenes in the house first and then we moved out to the beach for the Elliot and Bernadette sand castle [scene]; we shot the scenes with Elliot and Bernie in the order that things aired in the episode.

We came back after the lunch break to shoot the scene with Bernadette and Olivia [in the restaurant]. We had been shooting in the morning with Ellen on the beach, in the sunshine, in that yellow shirt, and she’s magical, right? She’s electric. And she’s so full of life.

We’ve had some spectators all day long…[but] we were out there on the beach, and we moved inside. We were just about getting ready, getting [the set] lit, and I was with the director and one of the producers, sitting in one of the booths talking. And in walks this bag lady-looking person, who is curled in on herself, wearing a headscarf, looking frail and diminished and kind of crazy. And I look and I realize it’s Ellen.

But the producer looks over and he goes, “Hey, somebody get that crazy lady out of here! Tell her [the restaurant] is not open tonight.” And I had to put my hand on his arm and go, “That’s Ellen.”

I went over and talked to her, and she had decided to take off all her makeup and to come to set, because she felt, in her understanding of the character, that to come to that meeting with Benson, she had to have fallen off the emotional cliff in the aftermath of seeing Elliot and now be hanging on by a thread.

And, I mean, that is commitment to craft and bravery, especially for a woman who was of a certain age; that she would make herself as physically vulnerable as she was making herself emotionally vulnerable with the performance. It’s incredible.

I think we both know how hard it is to age on-screen in Hollywood and how brave it is to just age in the public eye. But let alone to transform her physicality, to make herself that vulnerable, and then to let her physicality also completely change. I mean, she looked half a foot shorter. It was like a string had been cut. The commitment to the craft and to the character—I remember it just being so phenomenally brave.

But this producer didn’t see her [at first]! But, I mean, that is Ellen’s commitment to craft—and that was 15 years ago. So pre-dialogue about women and beauty and identity and aging. Even in our current culture, in context, that’s a brave choice. 15 years ago? That’s f—ing heroic.

Obviously, she was awarded an Emmy for her role in the show. What did that mean to you to be a part of that?

It was stunning. I went to the Emmys with her and Brenda Blethyn, who was also nominated for an episode I wrote for her [“Persona”]. And my colleague Dan Truly was with Carol Burnett, who was also nominated for an episode he wrote for her [“Ballerina”]. So three of the five [nominations] were SVU.

At that point when she was nominated, obviously, the episode had come out and been seen by people. And we’d been nominated for a bunch of things, awards in mental health, and I got nominated for a Humanitas. The episode had received some very lovely support for dealing with bipolar and other mental health issues in public. And I’ve been really honored by that, but at the same time, almost any SVU of that era could have been nominated for dealing with something. We got nominated a lot for things because we were trying.

Ellen getting nominated was not a surprise, because her craft and her talent was so extraordinary. And her performance…it’s not what you expect to get in eight minutes in TV, especially in a pre-premium TV world.

Even today I don’t want to say well, she totally deserved to win because Brenda Blethyn! But Brenda Blethyn is a pisser; I love that woman. You want to be nice to all your children.

But I think that [Burstyn’s] dedication to the craft and what she brings, she’s one of those rare performers for whom you understand that this is more than a job. It’s a calling, it is a presence. This is her magic.

I remember being really relieved that it was a validation of the transgression against the format, so to speak. Because I think it definitely was one of many episodes that were recognized in different ways over the years, but they bought us freedom. I mean, this one was my favorite thing I ever wrote on SVU—there were other ones I really, really love, but this was my favorite. And I think that’s why there’s so many little bits of my flesh and bone in it—because I was writing about something that mattered to me, as well as to the characters.

LAW & ORDER: ORGANIZED CRIME — “A Diplomatic Solution” Episode 319 — Pictured: (l-r) Ellen Burstyn as Bernadette Stabler, Christopher Meloni as Detective Elliot Stabler — (Photo by: Zach Dilgard/NBC)

What does it mean to you that Bernie is still around in the LAW & ORDER universe?

I’m moved that this relationship between Stabler and Bernie is still continuing to be explored. Fifteen years ago, I set out to answer the question, “Why doesn’t Stabler talk about his mother?” with no idea it would/could ever move past the ending of “Swing”—which starts to unpack his reasons without moving any closer to a resolution or healing of the wounded mother/son relationship. As someone who cares about the character of Elliot Stabler, I’m excited to see how the story of Stabler and Bernie continues to evolve.

And it couldn’t be more wonderful to see more of the incomparable Ellen Burstyn. She is such a treasure, and any project she’s in is instantly elevated by her amazing craft, her humanity, her intelligence as an actor. And just as we saw in “Swing,” the chemistry between Ellen and Chris is electrifying to watch.

On a personal note, Bernie’s story as I began it comes from a tricky place in my own life. I grew up with a mother who lived with both mental illness and alcoholism, and our relationship was as fraught and sometimes as estranged as the Stabler/Bernie relationship. I wanted to write a parent/child relationship that reflected the nuances I had lived with—the hurt and betrayal on both sides, as well as the struggle to address the lingering effects of a traumatic or painful past on a present day relationship between adults. I tried to give each character relatable, authentic experiences—the same past events through two different lenses. So to see that relationship continuing to be explored—far beyond the 42 minutes and 25 seconds of run time I had for a single episode—it’s meaningful to me. After twelve seasons on the show, Bernie is a hell of a legacy to have left behind me.

–

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

RELATED:

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT: Amanda Green Looks Back at Writing ‘Swing’ (Part 1)

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT Season 24 Finale Recap: ‘All Pain Is One Malady’

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT Season 24 Finale: ‘All Pain Is One Malady’ Photos

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT’s Octavio Pisano Previews Velasco’s Team-Up with ORGANIZED CRIME’s Reyes

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT Recap: Carisi Spills a Secret, Benson and Stabler Reunite, and Muncy Gets a Win

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT: ‘Bad Things’ Photos

- 3 Teases for LAW & ORDER, SVU, and ORGANIZED CRIME

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT: ‘Debatable’ Photos

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT and ORGANIZED CRIME Set Three-Episode Crossover Finale Arc

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT Post-Mortem: Octavio Pisano on Velasco’s Big Decision and Proving His Loyalty to Benson

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT: Octavio Pisano Previews Velasco’s Reunion with Chilly

- NBC Renews LAW & ORDER, SVU, ORGANIZED CRIME, and ONE CHICAGO Trio

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT Scoop: A Case Hits Close to Home for Maxwell

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT Recap: What Secret Was Velasco Hiding?

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT: ‘King of the Moon’ Photos

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT: Mariska Hargitay Shares BTS Photos From ‘King of the Moon’

- The LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT Team Pays Tribute to Richard Belzer

- Cady McClain Dishes on Returning to LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT and DAYS OF OUR LIVES

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT Post-Mortem: Maurice Compte on Duarte and Olivia’s Different Approaches to Taking Down BX9

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT: Maurice Compte Previews Duarte’s Return to Take on BX9

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT: Octavio Pisano Teases Barba’s Return and an Unexpectedly Personal Scene Between Velasco and Carisi

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT: Pratibha Parmar on the ‘Real Gift’ of Making Her Network TV Directorial Debut with ‘Did You Believe in Miracles?’

- LAW & ORDER Stars Mariska Hargitay and Christopher Meloni Weigh in on a Potential Benson/Stabler Relationship: ‘It Just Has to be Earned’

- LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT: Warren Leight Explains the Cut Crossover Diner Scene

- LAW & ORDER: SVU and ORGANIZED CRIME: Mariska Hargitay and Christopher Meloni Break Down Olivia and Elliot’s Messy Reunion

Follow @GiveMeMyRemote and @marisaroffman on Twitter for the latest TV news. Connect with other TV fans on GIVE ME MY REMOTE’s official Facebook page or our Instagram.

And be the first to see our exclusive videos by subscribing to our YouTube channel.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases made through links/ads placed on the site.

Related Posts

Filed under #1 featured, SVU

Comments Off on LAW & ORDER: SPECIAL VICTIMS UNIT: Amanda Green Looks Back at Writing ‘Swing’ (Part 2)

Comments